Why Does the Western Left Worry More about Local Poverty than Global Poverty?

Though I care as little about riches as any man, I am a friend to riches because they are capable of good.[1]

– Thomas Paine

George Steiner once said that hope has always been on the Left. I suppose what he meant was that utopian thinking, and especially opposition to old social hierarchies, almost necessarily requires a break with tradition. Utopias on the Left have often been visions of more egalitarian worlds, and Leftist manifestos usually highlight injustice, especially economic injustice, including injustices that stretch across national borders. But in this century the Western Left’s focus is almost always on the marginalised in their own countries, and almost never, with the exceptions of anti-war opposition and climate change perhaps, on international solidarity. Why?

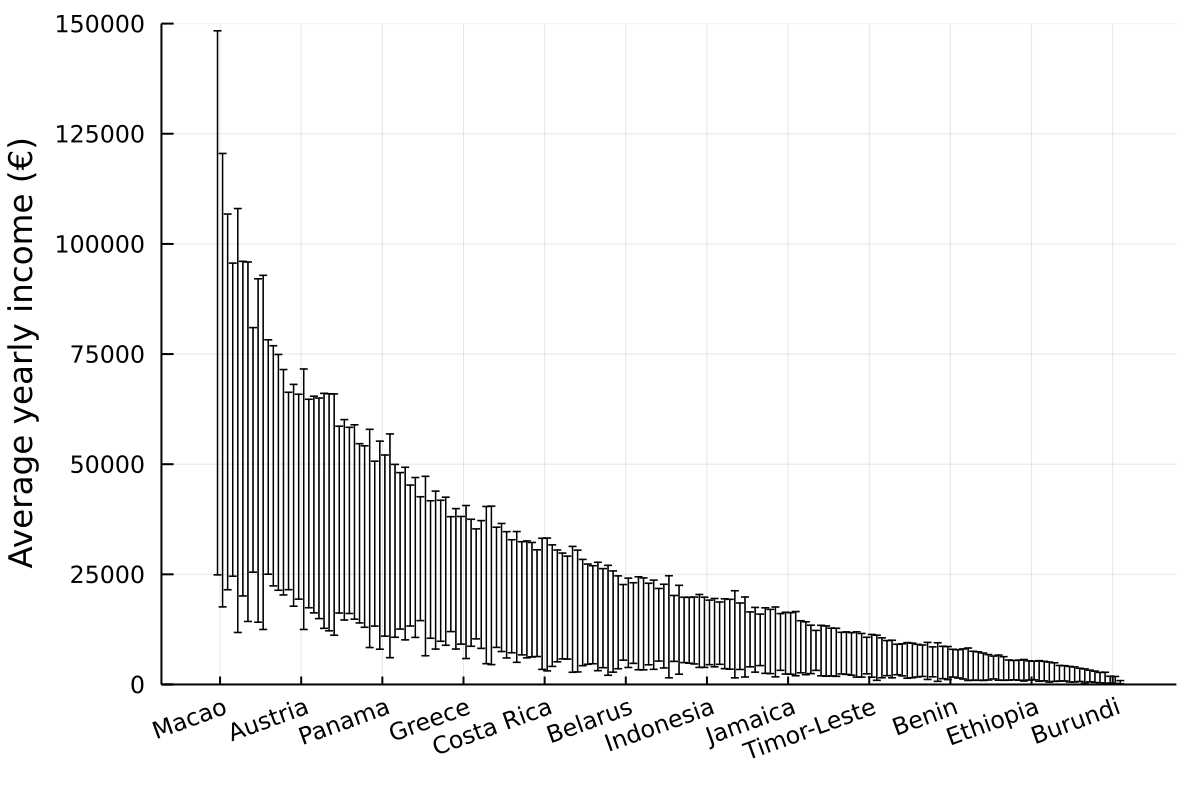

Inequalities between countries are far more substantial than inequalities within countries. Here is a plot of 179 countries, sorted by average national income per adult, using data from the World Inequality Database. It shows, for each country, the span between the average income of the bottom 50% of earners and the average income of the top 50% of earners (the spans are represented by thin vertical lines). If I have calculated this correctly, that means the working classes of many European, Australasian and North American nations have significantly higher incomes than even the wealthier halves of the poorest nations. The poorest people in this world, those who are most in need of support, do not live in Europe, Australasia or North America; they live in South America, Asia and especially Africa: the poorest 15 in this data set are all African nations.

But look at how much wider the gaps are in the rich nations! That means there is more income inequality in wealthier places.

Well, yes, that is true in absolute numbers, for the simple reason that there is far more money circulating there. But in relative terms the poorer nations seem just as if not more unequal than the rich ones. For example, in my native land, Sweden, the average income of the top half of earners is about three times as high as the average of the bottom half of earners; in Malawi, the ratio is about seven and a half to one. In the United States, widely considered one of the least equal Western nations, the average income of the top half of earners is six and a half times that of the bottom half; in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the ratio is seven to one. But the average income of a Swedish earner is 28 times as high as the average of a Malawian earner, and that of an American is 31 times as high as that of a Congolese!

I can go on. In the United States, the average income of a non-Hispanic white worker is one and a half times the average income of a Black worker.[2] But the average income of a Black worker in the United States is six times that of a working-age person from Africa![3] I am not saying that Black workers in America do not experience injustice or anything of that sort; I am saying that workers in Africa and other poor regions have really, really low incomes.

This becomes clear when we look at the same plot but with a logarithmic scale on the y-axis:

All right, but a euro goes much further in Malawi than it does in Sweden. A person with a poverty wage in the United States might do pretty well with that same wage in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

That is true. But these differences are an order of magnitude smaller than the income differences. One euro pays for about four times as many goods in Malawi as it does in Sweden; it pays for about twice as many goods in the Democratic Republic of Congo as it does in the United States.[4] Besides, this purchasing power difference is one more reason for people in rich countries to support people in poor countries, because a euro donated to a poor Malawian pays for four times as much as a euro donated to a poor Swede. Not only do the Western poor have much higher incomes than people in extreme poverty, but the latter, living in countries where goods are cheaper, are also easier to help.

Now, my home is somewhere on the Left, though some of my views may be unorthodox here. I think it is bad that people’s lots are determined to such a large degree by things out of their control, like the place and circumstances of their birth, their upbringing, the norms and institutions around them and even their genetic make-up. I think that those of us who are lucky have a duty to help those who are unlucky. I think that because those of us who are lucky, even though we have plenty, do not have infinite resources, we must try to do the most that we can with them. And I think this applies not only to individuals, but also to governments and political movements.

But any political party operates in a certain country. You cannot expect it to have as much impact when working internationally as it can at home.

You can just give money to poor people. For every 100 euro donated through GiveDirectly, 83 go directly to recipients.[5] About 725 million people still survive on less than 600 euro per year.[6] In 2020, the Swedish state spent 4.6 billion euro on foreign aid (around 0.38% of the state budget), compared with ten billion euro on health care and 25 billion euro on economic welfare for families, the elderly and people with disabilities or long-term illnesses. If Sweden increased its foreign aid spending by around 16% (an increase of roughly 723 million euro), it could bring a million people out of extreme poverty.[7] This is a great opportunity for a country of only ten million people. Why is it not a higher priority on the Left?

Well, historically, the West has done nothing but harm to the developing world, from colonialism on through neocolonialism. We should let the developing world get on with their business without interfering with it.

Colonialism and neocolonialism involve using power to extract resources or change behaviour. I am advocating giving people in extreme poverty unconditional aid. I fail to see how that does anything but empower these people; I can hardly think of a better way to keep control over somebody than to keep them in extreme poverty.

Even if everything you say is right, we cannot expect to unite people behind a goal like that, because they cannot easily relate to and empathise with people so far away and in such different circumstances. In order to gather the political force to actually do something, it is necessary to focus on more local and concrete domestic issues.

All Western nations already give significant sums of money to developing nations. So clearly there must either be popular support for doing so, or popular support is not necessary.

I think the point about relatability is useful in describing why the Left does not pay as much attention to global injustice as it does to local injustice, but I do not think it is a good argument in favour of doing so. For people on the Left, marginalised people in near countries may be considered the in-group in a way that marginalised people in far countries are not. But we are not supposed to put the in-group’s interests over the out-group’s, because that is tribalism.

Another reason I think this is neglected on the Left is that Leftist political parties, like all political parties, optimise chiefly for a single goal, namely to win votes in the next election. We know that because, in due course, the parties that do not, perish. People abroad cannot vote, and they cannot advocate for themselves in the West like marginalised people within those countries can, and so helping them will not be a high priority. But, again, while I think that helps us see why it is so, it is not a good reason for us to keep it so.

Even so, a state has special duties towards its citizens, duties it does not have towards non-citizens. The reason it exist in the first place is to serve the people that constitute it.

I think that is partly true, and might have been fully true had all nations been isolated from one another. But today, through trade, research, tourism and so on, Western nations benefit from people outside the West, including many who live in extreme poverty. That is one reason why I think Western nations have reciprocal duties towards people in poorer nations.

Here is another possible reason. If we as citizens of a nation decide that we want to help people outside our nation, then that should also be a goal of our state. The state can be what we want it to be. Whatever their relative merits, compared to implementing democratic socialism, a radical international cash transfer program seems almost trivially feasible.

Footnotes #

Paine, T. (2000). Agrarian justice. Alex Catalogue. ↩︎

I am not sure how reliable my source here is, but it seems roughly in line with other sources. The Department of Justice gives 32% more for non-Hispanic whites than Blacks, but because they provide only weekly numbers I prefer to use the former source. Either way, there is an order of magnitude difference between this disparity and the one between rich and poor nations. ↩︎

I am not sure whether the figure for Black Americans is of the average wage per worker, or if it is the average income per working-age adult. If it is the former, the ratio here may be somewhat smaller than six to one, as the number for Africans has the latter unit. ↩︎

See this table from Our World in Data. ↩︎

My source here is GiveWell. GiveDirectly’s website puts the number at 88 per 100, but let’s use the more conservative estimate for the sake of argument. ↩︎

More specifically, on 1,90 USD per day. That is the World Bank’s (contested) cut-off for extreme poverty. ↩︎

Yes, this is a rough calculation. There are questions about how much it costs to scale up existing programs and so on. And the whole concept of bringing someone out of poverty is elusive, because obviously not everyone starts out with nothing, and in some places the World Bank’s cut-off income is not enough to get by on. But I hope the calculation shows that it is orders of magnitude cheaper to support people in extremely poor nations than in Western nations. ↩︎